Heya!

So it’s been a while since I’ve created a post and admittedly, it’s because I forgot about this website and because I’ve been having so much fun developing Timeway. I’ll share another update post on the latest features soon, but for now I want to focus on one of the graphical limitations that I faced and how to fix it. This is going to get pretty technical by the way, so prepare for the most nerdiest nerding about 3D engines.

So a little backstory, when I was just getting started with the 3D world in Timeway (which I now named “The Pixel Realm”), I wanted to render flat objects in the world just like in early 3D games with primitive 3D engines. Once I had that implemented, the problem became immediately obvious;

Yikes, that looks horrible. For whatever reason, some transparent textures are cutting textures that appear behind them. I don’t have exact proof of what’s happening here, but I am 99.99% sure what the issue is: The textures (and polygons) are not sorted and the renderer is drawing non-opaque pixels into the z-buffer when it shouldn’t be.

What on earth do I mean by this? Well first, let me explain the visibility problem. If you already know about all that, you may skip the section below.

In 3D rendering, the order in which polygons are rendered is extremely important. Draw the polygons all willy nilly and you end up with far away models in front of close-up models. In short, without proper care in which order polygons are drawn, you end up with a mess. This is what is called the visibility problem.

However, back in the early days of 3D graphics, different games and different consoles had different ways of approaching the problem. The original Playstation simply used the “painter’s algorithm”; order the polygons you want to draw from furthest to closest and you’ve (mostly) solved the visibility problem. Of course, each game approached that in different ways, for example in Crash Bandicoot, most polygons in the stage are pre-defined and not sorted on the fly since the camera is always at a fixed angle, so this saves precious performance since not as many polygons need to be sorted.

Other consoles like the Nintendo 64 had a hardware feature called a Z-buffer; essentially you have a seperate framebuffer with identical dimensions to the main framebuffer, except this framebuffer stores the z-values of each pixel rendered. Each time a pixel is rendered, the current pixel in the z-buffer is tested against the pixel that is to be rendered, and if the pixel in the buffer has a greater z-value, the new pixel is discarded since there’s polygons overlapping the current one being drawn.

In Layman’s terms, it draws the pixels closest to the camera while discarding pixels that aren’t seen.

So, how does all of this tie into the issue in Timeway? Well, from the screenshot, we can see that certain pixels in some of the far-away textures are not being drawn. When drawing to a Z-buffer you shouldn’t draw completely non-opaque pixels as this can cause issues we can see. But for whatever reason, it looks like there’s some bug in OpenGL or the Processing framework.

There’s no way I’m going to dig into the source code of OpenGL or Processing as this could break so many things. So we’ll do the next best thing; sort the textures. Plus, z-buffering has problems when it comes to transparent textures, that of which can be solved by sorting the polygons. So hey, we’re killing two birds with one stone.

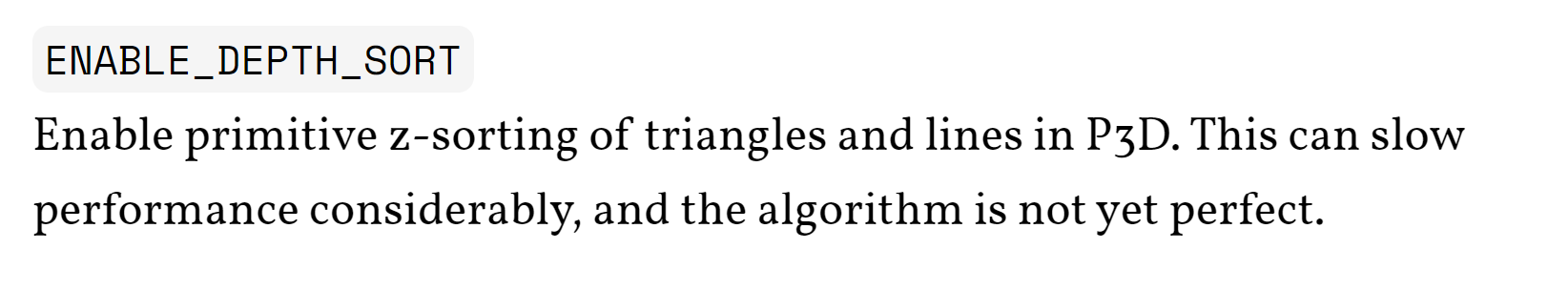

Luckily for us, there’s a function in the Processing framework that does just that for us:

…ok, so it clearly states that it’s not perfect, but we’re only rendering at most, what? 400-600 polygons on screen at any given time? So surely it can’t be that bad, right…?

…aye yai yai. No, that’s not your browser struggling to play the video (I hope), that’s the actual performance of using that sorting function in Timeway. That is painfully slow. Sure, having OBS Studio running on my measly Surface Book 2 did make it slower than it actually was, but still. An original Playstation could render something like this way faster, and this is running on modern hardware!

So, that means we need to write our own sorting function. At first I was really skeptical that I could actually make something that would work, but as it turns out, it wasn’t too hard.

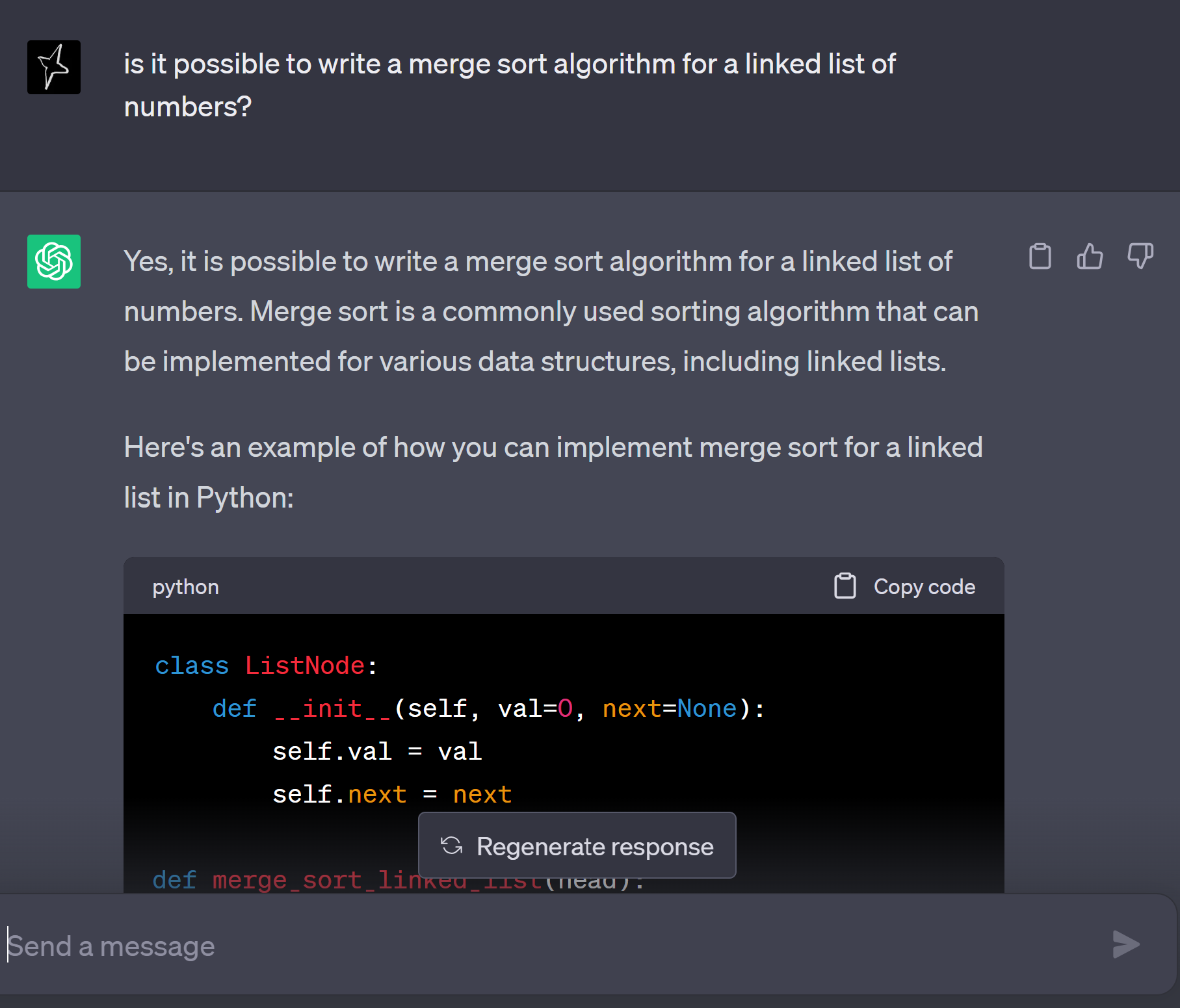

First, I implemented a linked list for all objects rendered on the scene. The ground is not included because it’s perfectly flat and doesn’t require any sorting. Then, like all lazy programmers, I asked ChatGPT for my favourite sorting algorithm; merge sort.

Of course, I “tweaked” the code by asking ChatGPT to write it in Java and such. I chose a linked list implementation because I didn’t want to create loads of garbage objects by regenerating an ArrayList each time, with a linked list you simply swap around items without creating new objects.

After, I wrote code to add each object to the list as it runs the logic, then when it comes time to render everything, it merge sorts the list of objects from furthest to closest, and then displays the objects in our sorted list.

And it worked great! All of the textures were being displayed correctly and it seems like the issue was solved!

Honestly, I was expecting it to give me a massive headache since sorting tends to be quite processor-intensive. But nope, it works well!

…but of course the story doesn’t end here.

See, another reason I used a linked list is because once the list was sorted, it can be carried over to the next frame. Each time the player moves, the list only needs to be slightly sorted. Unless the player teleports, only slight changes to each object’s positions are made.

So basically what I’m trying to say is, I expected a big-o notation of almost O(n) since most of the process involves checking if the list is still sorted the next frame.

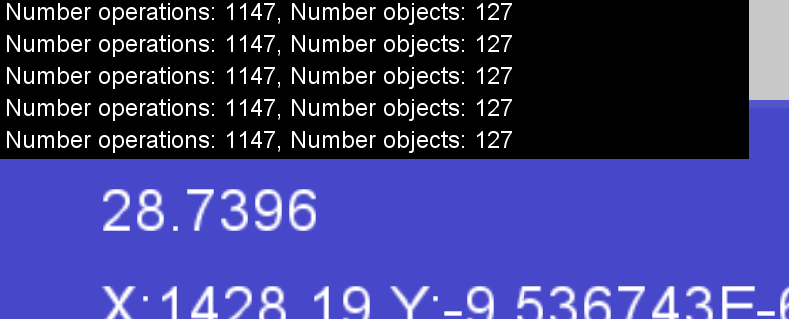

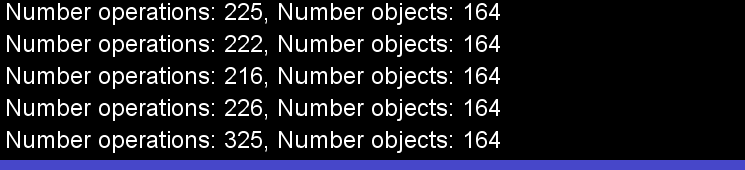

However, I decided to test that theory with merge sort by checking the number of operations performed:

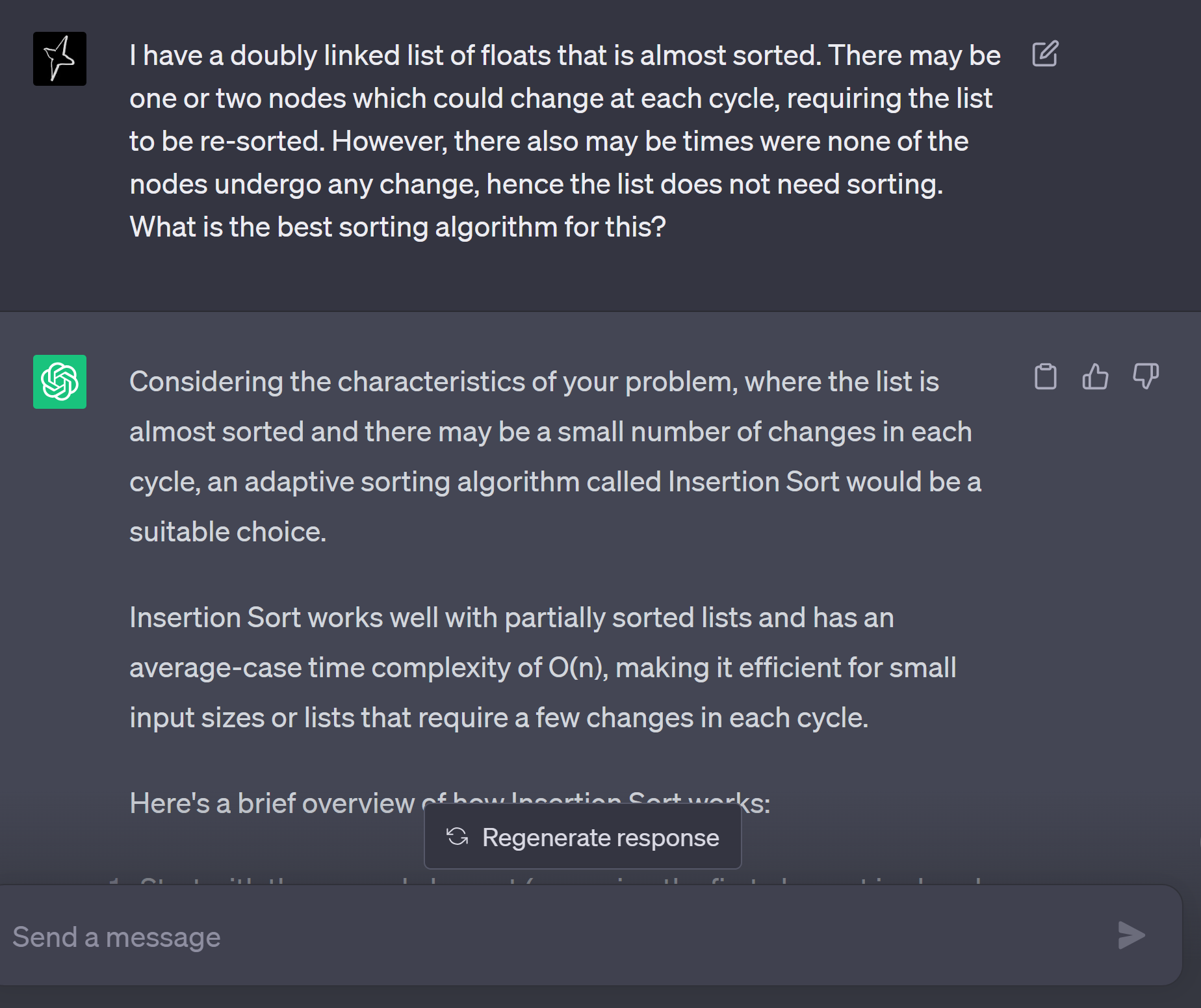

I mean… technically, it’s still a complexity of O(n log n), as when I move about in the world, it increases almost linearly. However, that’s still a large number of operations, and it doesn’t seem to be O(n) as I’d hoped. So that’s when I decided to re-code a few things and of course, ask ChatGPT yet again for answers.

This answer surprised me at first. Isn’t insertion sort supposed to be an ineffective algorithm? I thought. Remembering the uni lectures we’ve had, it has an average complexity of O(n^2), which is undesireable in pretty much any computing circumstance.

But then it began to make sense when I thought about it; it works by traversing the list from start to end, then it swaps unordered objects, going backwards until they’re in the right order, and continues from that point.

In an almost sorted list, say you have 1 or 2 objects in a list of 100 that are off. That means that it would go through the list and not spend too many cycles sorting the 2 objects that are off. Most of the time is spent pretty much checking if the list is still sorted which is a big-O notation of O(n). Perfect!

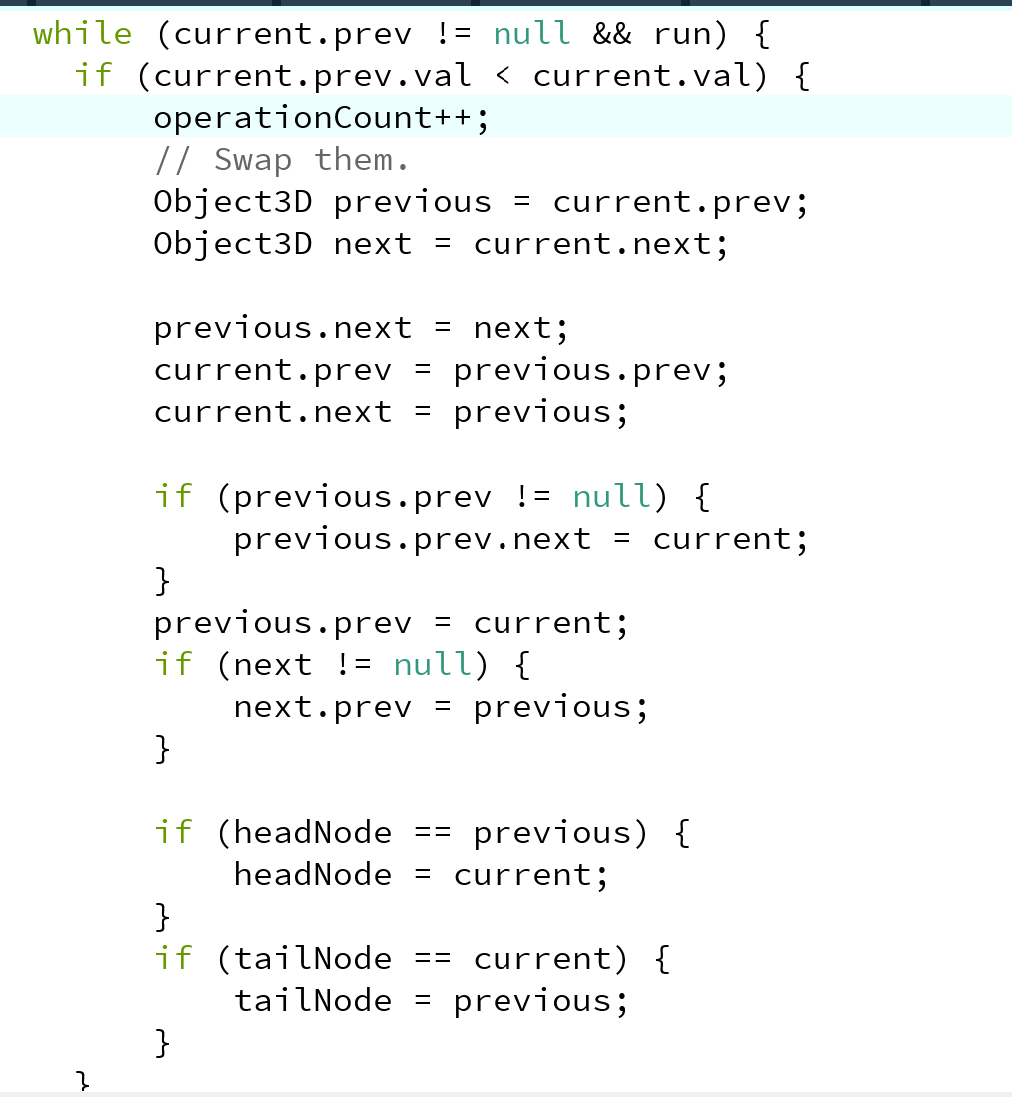

So again, I asked ChatGPT for an insertion sort algorithm and that’s when the actual headaches began. The algorithms it spat out kept breaking up the linked list (resulting in objects suddenly disappearing in the scene). At one point it worked but the big-O complexity was very much NOT O(n), so that’s when I had to write it myself. And let me tell you, writing an algorithm that deals with linked lists is pure torture.

Above is a snippet of the insertion sort algorithm. Pretty simple stuff, right? (sarcasm).

I tried asking ChatGPT to help solve some bugs, but even it kept spitting out incorrect answers. People keep saying that AI is going to take over programmers and people’s jobs, yet it can’t even write a common working algorithm! I don’t think there’s much to panic about here!

But, finally, I managed to get it working, and these were the results:

When stationary:

When moving:

If I had a photo of my face when I saw these numbers I would’ve put it here. These results were amazing. We went from thousands of operations to pretty much the operations being parallel with the number of objects in the scene. Success!

Now I know what you’re thinking. Did this actually have any noticeable impact on the framerate?

The answer is no, haha. Truth be told, it was already plenty efficient for the hardware it was running on with the merge sort algorithm. The reason I went through all this effort to get it as efficient as possible is because

A. We might have hundreds of thousands of objects in the future (e.g. with particles), and having an efficient algorithm saves us the hassle of that in the future.

B. The satisfaction of micro-optimising this makes it worth it even if there’s not really a noticeable difference.

C. It was a learning experience.

Seriously, before doing this, I knew that most games on the Playstation used a linked list approach like mine for sorting the polygons. But at the time I knew that sorting algorithms were very expensive on the processor, especially for the 33MHz processor on the console, so how games were even able to achieve this was a mystery to me. Turns out, you just use the right algorithm, then you’ll be able to achieve almost O(n) complexity!

And also, it taught me a valuable lesson about coding; don’t judge an algorithm by its worst case O(n). Different algorithms are good at different things. Choose the right one for the job.

Thank you for reading! Cheerio!